This three-part series explores how the environmental consulting industry is adapting its due diligence practices following the publication of ASTM E1527-21 and the classification of PFAS as a hazardous substance by U.S. EPA under CERCLA. Take a look back on part 1—how the industry’s evolution to assess PFAS risk has progressed—and part 2—highlighting how the industry is incorporating PFAS risk assessments into their Phase I ESAs—of the survey results if you missed them. Each part examines the results of the LightBox 2024 Benchmark Survey which focused on specific research and reporting strategies that support clients identifying PFAS risks and if those risks are impacting commercial real estate transactions.

This third and final installment of our series dives deeper into how environmental professionals (EPs) are reporting PFAS risks within their Phase I environmental site assessments (ESA), as highlighted in the LightBox 2024 Benchmark Survey. With the designation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) as hazardous substances under CERCLA and the growing awareness of its impact on commercial real estate (CRE) transactions, this article explores how the industry is adapting reporting methods and managing potential PFAS-related deal disruptions.

Varying Approaches to PFAS Classification

When survey respondents were asked how they label known or suspected PFAS conditions on a property in Phase I ESA reports, their answers highlighted the range of outcomes from property to property. While nearly 29% classified PFAS as a Recognized Environmental Condition (REC), and 4% considered it a Business Environmental Risk (BER), and a significant majority (56%) responded that it depends on the property location, history, and present conditions.

This variability reflects the complexity of PFAS reporting. One respondent noted that the classification often hinges on site-specific factors, stating, “It depends on the location of PFAS relative to the subject property and the exposure risk present.” Another explained that PFAS is labeled as a REC only if the site is a contributor, whereas it is treated as a BER if it is not.

These findings underscore the evolving regulatory landscape and the need for flexibility in assessing PFAS risks. As one respondent put it, “Environmental professionals must tailor their approach based on regional regulations, compound-specific risks, and operational contexts.”

How do you label known or suspected PFAS conditions in your Phase I ESA reports?

Limited Recommendations for Phase II Assessments

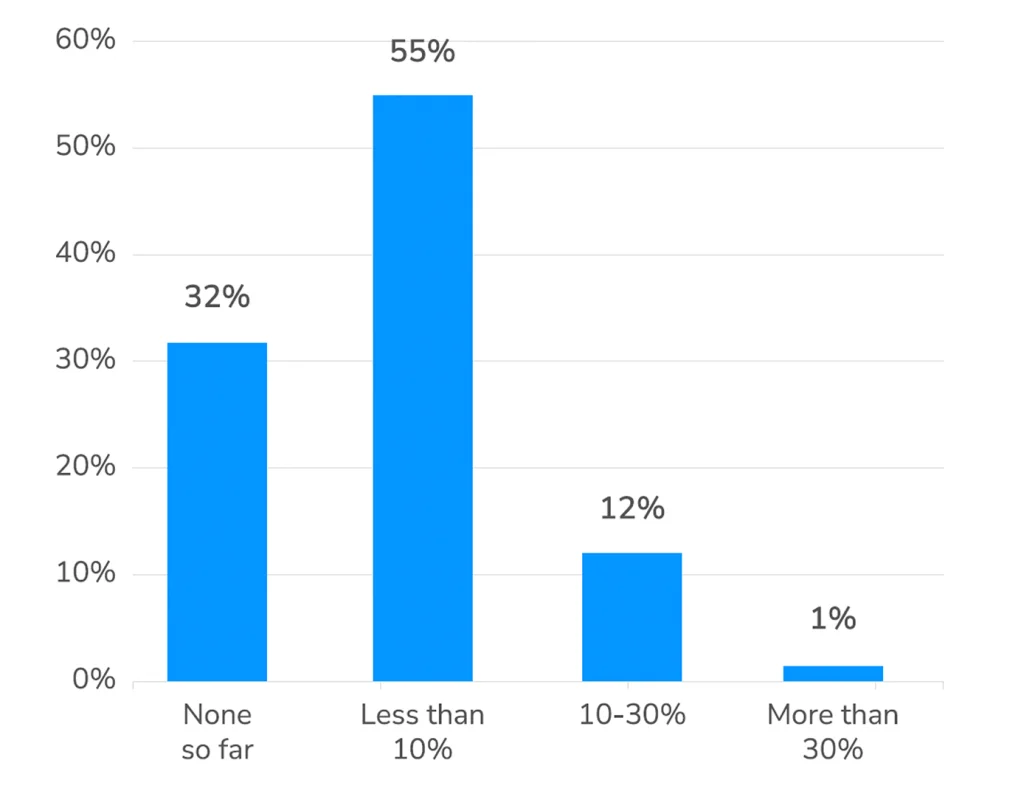

The survey also revealed that recommending Phase II environmental assessments for PFAS remains relatively uncommon. Over half (55%) of respondents reported recommending Phase II assessments for PFAS in fewer than 10% of cases, and only 1% indicated making such recommendations in more than 30% of their projects.

These testing recommendations are more likely in high-risk scenarios, such as properties with a history of industrial activity, dry cleaning operations, or car washes. However, as one respondent observed, “There is often pushback when evidence of a potential PFAS release is less definitive.”

This cautious approach reflects the industry’s hesitancy to incur additional costs or delays without compelling evidence of onsite PFAS contamination or offsite contribution to a neighboring property condition.

What would you estimate is the approximate percentage of your Phase I ESA projects that include a recommendation for a Phase II to further investigate PFAS risk?

PFAS Impact on Commercial Real Estate Deals

While 70% of respondents reported that PFAS has not yet disrupted transactions, the remaining 30% indicated that PFAS risks have impacted some CRE deals. For example, one respondent shared, “As long as the property is serviced by municipal water, it hasn’t been an issue. But for properties with well water, additional testing is often recommended. If PFAS is present in the well, buyers may walk away from the deal.”

When asked about deal outcomes, another respondent noted that only sophisticated developers seem to prioritize PFAS risk assessments, while others remain less concerned. However, a few reported losing deals outright due to PFAS findings, emphasizing its potential to influence decision-making in the CRE sector. One respondent noted that “Clients involved in acquisitions are much more concerned with PFAS risk than lenders involved in refinancing.”

If PFAS are impacting deals, which of the following types of transaction outcomes have you experienced?

A Proactive Path Forward

The LightBox 2024 Benchmark Survey revealed an industry still acclimating to the challenges posed by PFAS due diligence. Environmental professionals must navigate varying state regulations, educate clients on emerging data and practices, and balance the need for PFAS risk evaluation with the practical realities of CRE transactions.

As PFAS research advances and regulatory frameworks solidify, the industry will be better equipped to adopt a consensus on consistent methodologies for assessing and reporting PFAS risks. In the meantime, there is little doubt that inclusion of PFAS into ESAs is the new standard and firms can better serve their clients by staying informed and adapting to these changes.

This series has highlighted how environmental consulting firms are changing due diligence practices to help clients manage PFAS risks effectively. As awareness grows, proactive management of PFAS risks will be a key to protecting property values, mitigating liability, and fostering client confidence in an increasingly complex regulatory environment. For more insights into environmental due diligence trends, tune into the LightBox Environmental Due Diligence podcast.