- A LightBox webinar on broadband implementation revealed the central role mapping plays for states seeking to expand service to underserved and unserved areas

- With accurate maps, states save money by targeting the regions most in need of service and providers save by avoiding unnecessary engineering and buildout work

- Working with partners such as LightBox can help states educate the policymakers who determine how expansion efforts will proceed

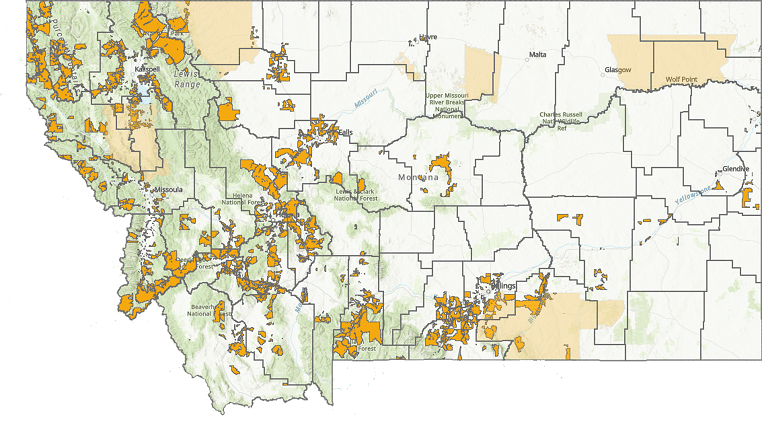

Closing the digital divide is a significant goal for legislators in Washington, D.C. As states such as Montana mobilize to take advantage of federal funds to expand broadband coverage to underserved and unserved areas, LightBox is helping them develop precise maps that are crucial for success.

During a recent LightBox webinar, “Key Learnings and Best Practices in State Broadband Implementations,” State of Montana broadband program manager Chad Rupe and chief data officer Adam Carpenter discussed the importance of detailed location-level data, managing a wide range of stakeholders, best practices, and lessons learned with LightBox vice president of government solutions William Price and director of state broadband mapping Robert Szyngiel. Sherrie Clevenger moderated the discussion. Below are summaries of each topic covered.

Topic 1: From Montana’s perspective, why is accurate location data and mapping so crucial for helping close the digital divide, and what has been the challenge of identifying broadband accuracy?

Chad Rupe: Identifying the fabric of broadband serviceable locations is very important. We want to make sure we’re not overlooking underserved neighborhoods and communities. Maps like those we’ve developed with LightBox have helped us overcome challenges in identifying these areas. With the level of funding available and suitable maps, we can close the digital divide.

Adam Carpenter: Building out broadband is an infrastructure program with enormous scope and challenges. Mistakes are incredibly costly, so knowing where serviceable buildings are located is crucial—we don’t need to deliver broadband to a grain silo.

Topic 2: “Don’t Overthink It.”

AC: Infrastructure projects are complicated. The larger things get, the harder it is to keep track of the scope, which creates a tendency to overthink and make assumptions. The best way to approach it is through “iteration”—you peel off pieces as you go, and what’s underneath is slowly revealed. Building the map is the first step in this process.

CR: You must have a specific purpose for what you’re trying to do with a map, but you don’t need all the answers right out of the gate. Keep it simple. Organizations often take a “waterfall” management approach to projects and that’s why they fail—too much is happening at once. An innovative, agile approach allows you to deal with various challenges as they arise.

Topic 3: What’s the cost of inaccurate, wrong, or too little data for the state and/or its citizens? What are the implications for the ISPs that may be applying for grants?

CR: Incomplete data can hamper a provider’s efforts to improve service based on the available funding because many census tracts would be considered served even when they aren’t. It’s important to have a strong GIS team, as much data as possible, and accurate maps. Most states are good at building infrastructure, but not necessarily at building broadband—it’s a unique challenge.

AC: Government funds and grants to do buildout are restricted. If we don’t have accurate information and the ISP doesn’t either when it starts work in some area, the federal government could claw back money. It’s a big deal if you dig 30 miles of trench that you didn’t need to dig, especially if you lay cable in it. It’s important to avoid engineering parts of a buildout that won’t eventually be completed.

This is an area where there’s strong synergy between public and private efforts. No private entity, at least in the telecom industry, could have put our map together because the ISPs aren’t going to share their data and there’s public data to which they may not have access. Working with a company such as LightBox increased our ability to effectively plan by bringing together information from both sides.

Topic 4: What benefits do local governments, state and federal governments, and providers gain by working with a qualified commercial data provider?

AC: Enormous benefits. No state should embark on this process without working with an experienced partner like LightBox. You have to figure out which locations need to be serviced and also understand the myriad state rules and regulations that will help or hamper the effort. You have to gather as many datasets as possible and combine them, know what insufficient data looks like with regard to that space, which business rules apply, and what the best practices for the broadband space are. Managing this kind of complexity requires a partner.

CR: You don’t need to reinvent the wheel. I would tell governments, don’t try to learn your own lessons, learn from other people’s mistakes and successes. Working with a commercial data provider got us out of our internal government silo and sparked creative thinking. Third-party, impartial maps also helped remove politics from the equation—we could focus more on solving the problem itself and less on the politics of solving the problem.

Topic 5: Why is it so important for states to be able to stand up an accurate view of their broadband maps as quickly as possible?

AC: Getting these projects done could take five or ten years—and that’s not counting extra lead time on raw materials, many of which are hard to acquire right now. There are deadlines for using federal funds. Time is money. You can’t overstate how vital shaving 12-18 months off a set of projects is. If one project, one buildout, gets delayed by 12 months, that’s one thing. But a slow rollout of maps could delay 25 or 30 potential projects by that amount of time.

CR: These maps have an impact on policy. The longer it takes to develop a map, the longer it takes for policymakers to understand the problem and determine how to solve it. Not having data to counter inaccurate FCC maps could limit funding and impair our ability, and the power of providers, to make sound decisions. States also need to train a workforce. The quicker you have maps, the better you can identify potential opportunities and avoid problems.

Topic 6: What were some challenges—expected or unexpected—with respect to the policy making for broadband in Montana?

CR: Inflation was an unexpected challenge—the cost of materials has gone up since the pandemic. Another challenge was educating policymakers, many of whom are essentially part-time government workers tasked with understanding a host of issues, not just broadband coverage. It can be difficult to keep them engaged. We also had to ensure we didn’t violate congressional intent, and that we were good stewards of the federal funding.

AC: Dealing with policymakers can be a challenge. I would advise them to set the project’s goals, objectives, and guidelines but avoid overly prescribing how to administer it. Things change rapidly on the ground, especially in the tech space. It’s crucial to allow administrators and project managers the flexibility they need to complete the project with the best technology and resources available.