It can be risky business these days for small community banks under intense regulatory scrutiny. When banks provide financing for commercial real estate property purchases, they enter a complex web of risk management and regulatory compliance. As regulations for financial institutions become more stringent and complex, many small banks find themselves scrambling to put formal risk management policies in place. If this sounds all too familiar, keep calm and read on. LightBox EDR® is here to help with this Tip Sheet on best practices for environmental policy development. Below is an overview of the essential elements that must be considered when developing a policy to address environmental risk.

Regulatory Focus on Environmental Risk

When CERCLA was signed into law in 1980, it triggered a new phase of managing environmental risk by making owners, and potentially lenders, liable for property contamination. Since then, environmental due diligence practices by commercial real estate lenders have continued to evolve—as have guidance, policies and regulations.

In the wake of the financial crisis, regulators are placing greater emphasis on proactive procedures to manage risk and minimize liability due to a perceived over-concentration of commercial real estate risk. In the words of one Senior Manager of Environmental Risk at a national/international bank, “In general, there is more emphasis on risk management in the field than before the financial crisis. Here at our bank, we request many more risk assessments than we were five years ago.”

For a financial institution, a well-constructed environmental risk management policy can satisfy the guidelines and requirements of federal regulators, such as the FDIC and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. In 2013, the OCC issued detailed guidance to the banks it regulates outlining the specific elements needed for an effective environmental risk management policy. The document also includes an Internal Control Questionnaire related to environmental management to gauge how comprehensively an institution’s policy for lending, foreclosing and monitoring environmental risks is protecting the bank’s exposure to liability. For example, the questionnaire asks if there are policies in place to ensure that the bank:

- Identifies, evaluates and monitors potential environmental risks associated with its lending operations;

- Establishes procedures to determine the extent of due diligence necessary to protect the bank’s business interests; and

- Assesses the potential adverse effect of environmental contamination on the value of real property securing its loans, including any potential environmental liability associated with foreclosing on contaminated properties.

Also notable in the OCC guidance is the regulator’s list of what banks should address in any “effective environmental risk management program.” For risk managers writing their first policies, the list is widely-regarded as a valuable starting point. It prescribes 18 specific policy elements, such as a tiered approach to environmental due diligence that gives special attention to the U.S. EPA’s All Appropriate Inquiries rule, reliance on qualified environmental professionals with adequate training and experience, property monitoring over the course of a loan and maintaining adequate loan documentation. It is important to note that headlines of late make it clear that the OCC is serious about ensuring that the institutions it regulates are adhering to sound risk management policies and practices in accordance with guidance. When the guidance was released, some banks with policies already in place reviewed and revised their policies in accordance with the OCC’s more prescriptive guidance.

Beyond Regulator Scrutiny

Bank regulations are not the only reason to build a strong environmental policy that defines due diligence requirements, responsibilities and accountability. There are also strong business reasons for the bank and its borrowers. A good program, if properly implemented, can help protect the lender from situations in which the borrower is unable to repay the debt due to environmental risks or impair the bank’s ability to recover funds in the event of loan default. It can also help protect the bank from CERCLA liability exposure.

“The purpose of having a proper environmental risk management program is not simply to satisfy regulatory compliance. The real goal of any program is KNOWING. Knowing what risks are present, knowing who will address those risks, knowing how to mitigate those risks and finally, just knowing what needs to be done. Knowing is what will protect the bank, and in the end, the customer.”

~Brian Ginter, Director / Senior Consultant at Pyramid Real Estate Consulting Network, LLC (formerly at Burke & Herbert Bank).

Some overlap exists between the risks faced by borrowers and those faced by lenders. Financial burdens may be caused by contamination cleanup, fines and penalties, and construction delays due to loss of permits. If a bank wishes to sell a property with known contamination used as collateral, it may be stuck making an unfavorable deal at a loss. Additionally, lenders may shoulder the liability under some environmental laws, such as the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, OSHA and others.

Advice for Building a Solid Environmental Risk Management Policy

A lender writing a policy for the first time has a number of questions to answer such as:

- What is our appetite for risk? How much are we willing to accept?

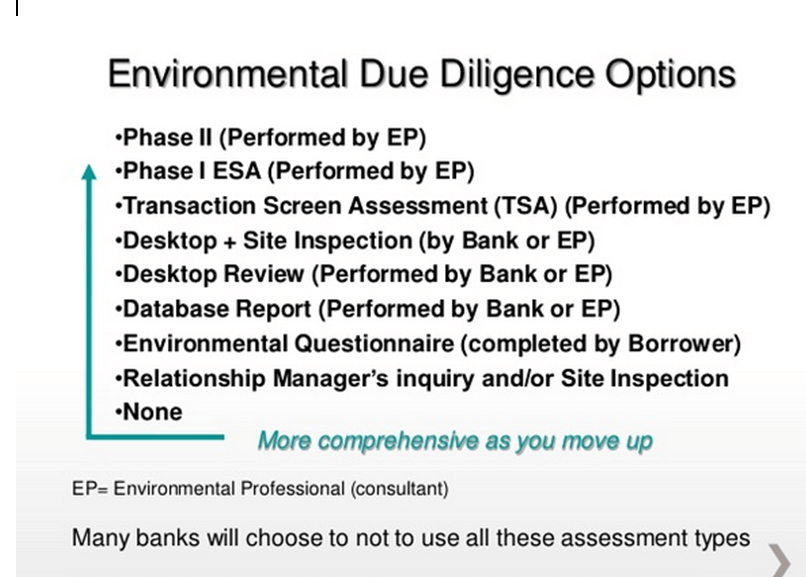

- What types of environmental due diligence do we want to require (e.g., borrower questionnaire, Transaction Screen, SBA Records Search with Risk Assessment, Phase I ESA, etc.)?

- Do we want different requirements for new originations vs. refis or foreclosures?

- Do we have environmental expertise in-house or are we relying exclusively on outside experts?

- What are the risk management regulations that apply to our institution?

- What do other types of lenders of comparable size require in their environmental policies?

Mike Tartanella, Environmental Risk Manager, Capital One, offers this advice for getting started:

“A risk manager at a smaller institution first needs to decide if their transactions require—or if the institution is seeking—any of the three CERCLA protections. If the answer is ‘Yes, we need CERCLA liability protection,’ then the policy path is clear and straightforward [under the federal All Appropriate Inquiries rule].

“If they decide that CERCLA protections are not required at their institution, then they can customize their policy to reflect what they want to accomplish. But the latter choice should still utilize industry standards such as database searches and reviews, transaction screens, Phase I environmental site assessments, etc. The policy should not seek to reinvent the wheel, but rather should be tailored to that institution’s requirements utilizing industry standard instruments and procedures.”

When writing a policy for the first time, don’t overlook the insight that first-person experience can afford.

“The most valuable piece of advice I’d offer someone at a community bank is to reach out to the full-time environmental risk managers at national and regional banks. My experience has been that environmental risk managers are generally quite generous with their time and advice. From their perspective, it is in the larger banks’ best interest that smaller banks apply best practices in environmental due diligence.”

~James King, VP, Environmental Risk Manager at Fifth Third Bank

Best practices in lender environmental policy development include:

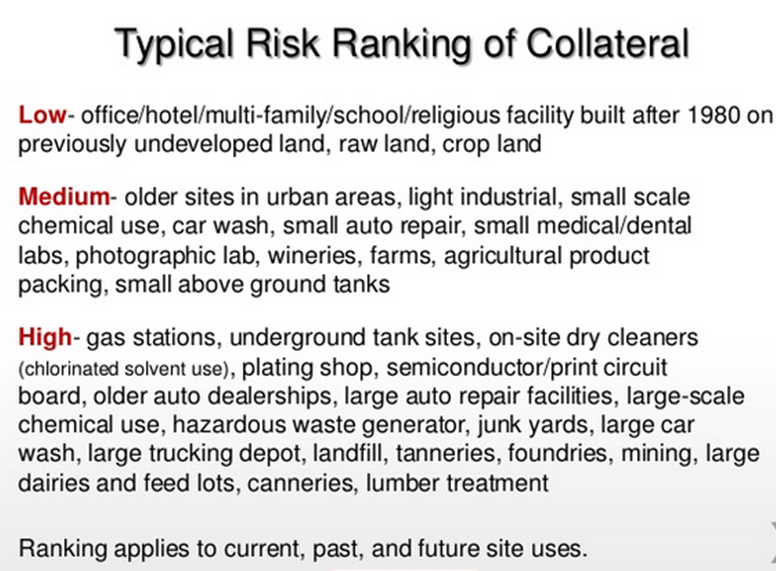

- Define a tiered approach to due diligence—This can take the form of a matrix with loan size and property type along one axis and required due diligence steps along the other. When thresholds are set, a matrix resolves potential confusion and establishes a clear definition of risk categories and loan thresholds.

- Integrate multiple levels of due diligence into the risk matrix—Options can be set that start with a low-level inquiry and/or site inspection by the bank for properties with low-risk uses, and escalate to more extensive environmental due diligence for loans on properties with high-risk uses:

- Define low- and high-risk sites’ uses to use as a guide for assigning low vs. higher levels of environmental investigations. The U.S. SBA’s environmental policy uses a widely-used NAICS code list of high risk industries that can be valuable in policy writing. Below is the example used by Georgina Dannatt, VP Environmental Risk Manager, Bank of the West, in EDR® Insight’s webinar on critical elements of environmental policy development:

- Rely only on qualified environmental professionals—The U.S. EPA’s AAI rule offers a widely used definition for “environmental professional” with specific requirements for years of experience and education (The definition is also part of ASTM’s standard for Phase I environmental site assessments (E 1527-13).

- Include mitigation measures—Options include holding back funds for future cleanup needs, making the loan without using a property as collateral or requiring environmental insurance in certain cases.

- Define shelf life of past due diligence—In some cases, a previous Phase I ESA report may be available so it is important to define rules for when past investigations are acceptable.

“Our policy requires us to pull a new Phase I for every new transaction, one year or younger and we can re-use it, but other than that, our borrower has to get a new one.”

—VP, Special Assets Manager, Community Bank

- Establish clear documentation requirements—Be sure that due diligence is being documented consistently, especially across bank branches and that any exceptions to policy are being documented and justified.

- Assign responsibility—Regulators want to know there’s more than a policy. Examiners also look for implementation procedures. Who is responsible for oversight? For ensuring the policy is followed?

- Don’t overlook training—A policy will only be effective if employees are trained in following it and there is “buy-in” throughout the organization, including support from senior management and a willingness to enforce the policy.

- Conduct annual policy reviews—To address changing regulations and economic fluctuations, the policy should include a mechanism for regularly review the policy and procedures for necessary updates.

Moving Forward, Cautiously

Every lending institution, regardless of size, must engage systematically in environmental risk analysis as part of protecting the institution from liability exposure and avoiding any loss of collateral value. The overlying purpose of an environmental risk management policy is to ensure that environmental risks are fully understood by the lender when underwriting property loans. Each situation must be individually reviewed because balancing risk and value is never a simple equation. The existence of contamination (past or present) does not necessarily mean a lender will not allow a property to serve as loan collateral. Likewise, just because borrowers or their consultants feel that a particular environmental risk is acceptable does not mean the lender must also find it acceptable.

The way that institutions manage risk has undergone significant changes since the start of the market downturn, in response to a mix of regulatory and economic forces. The adoption of more environmental policies at the smaller end of the bank-size spectrum is a positive development. Formal policies are an effective way to manage regulator pressure, protect the bank’s own liability and that of its borrowers, and adhere to industry best practices. In addition, there are more eyes on risk management today than ever before, so consistency and having an established process in place communicated throughout the institution are critical for effective implementation.

Resources

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Commercial Real Estate Handbook, August 2013.

- FDIC’s Guidance for an Environmental Risk Program

- OTS bulletin on Environmental Risk and Liability

- U.S. SBA’s Environmental Guidelines (SOP 50 10 5(g)

- EDR® Insight’s Top 10 FAQ on Lender Policy Development

- EDR® Insight webinar: Learn from the Experts–Critical Elements of Effective Environmental Policies (see slide 31 for a Sample Policy Matrix provided by Georgina Dannatt, VP Environmental Risk Manager, Bank of the West)

- EDR®’s Sample Environmental Policy Matrix for Lenders

- Federal All Appropriate Inquiries Rule (40 CFR Part 312)

- Environmental Bankers Association